Stories

Father fish and rodent drivers: New Biology Faculty Member Has Seen It All

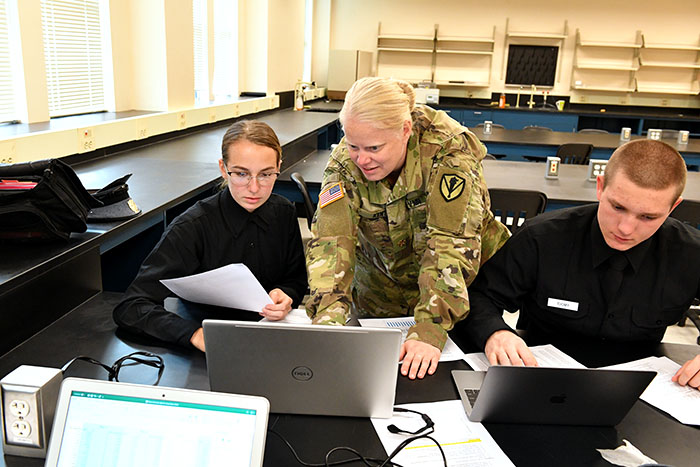

Maj. Molly Kent helps cadets with data analysis in an introduction to biology class.—VMI Photo by Mary Price.

Move over, zebrafish—there’s somebody new swimming in the tank.

Many VMI alumni and current cadets will remember the research that Col. Jim Turner ’65 conducted on zebrafish—but now that Turner has retired, the newest member of the biology department faculty, Maj. Molly Kent has arrived, with plans to bring to post a different species of fish.

Kent, a behavioral neuroscientist, is interested in the three-spine stickleback—a fish species in which the father assumes almost total responsibility for raising the young.

According to Kent, only about 6 percent of fish species are paternal-only. That’s attracted many scientists—but there’s a research gap Kent is eager to fill.

“[The stickleback’s] behavior has been really well studied,” noted Kent. “Very few people have studied the brain.”

Kent added that a procedure known as Golgi staining, which enables the study of neurons under a microscope, hasn’t yet been done in the stickleback. “That’s something that’s really great for students to handle,” she commented.

Kent got her start in neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin, where she earned an undergraduate degree in biology. She’d entered the university thinking she’d major in psychology, but meeting a professor who was a neuroscientist changed her mind.

“I took my first [psychology] class, and I decided ‘no,’” she explained. “I liked biology, and when I realized I could combine both psychology and biology, it was the best of both worlds.”

Before she came to VMI, Kent was a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Richmond, where she was involved with research that gained national and even international attention when it was published in the journal Behavioural Brain Research in mid-October.

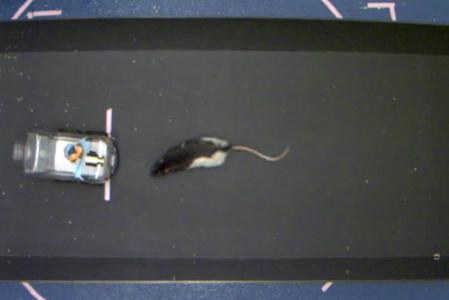

There, Kent worked under Dr. Kelly Lambert, professor of behavioral neuroscience, to see if laboratory rats could be trained to drive a tiny, rat-sized car.

Like most neuroscientists, Lambert keeps rodents to study their behavior, with the goal of extrapolating what’s learned to humans. One day, Kent recalled, a psychology professor asked, “Can we get rats to drive a car?” Kent explained that the professor was really just thinking out loud, but since Lambert had a pair of rats available—ones she’d dubbed Mario and Luigi—and another professor was willing to design a tiny vehicle for them, they decided to give it a try.

All of the women came to the experiment with a solid knowledge of rodents—and what really matters to them. “Rodents are extremely food motivated,” said Kent. “You can train them to do just about anything for food.”

All of the women came to the experiment with a solid knowledge of rodents—and what really matters to them. “Rodents are extremely food motivated,” said Kent. “You can train them to do just about anything for food.”

Lambert and Kent started slowly, giving the animals a tiny bite of sweet cereal when they entered the vehicle. Gradually, more behaviors were introduced and rewarded, so the rats learned to stand on the metal plate on the bottom of the vehicle and hold onto copper wire. When they did so, that moved the vehicle forward and toward a food reward.

But that wasn’t all. Later, the rats learned to turn the tiny cars to the left or right by touching the sides of the vehicle. “How quickly they were able to catch on was extremely surprising to me,” said Kent. “The steering I didn’t exactly expect to happen. It was interesting that they could figure out, in space, how to move an object to move themselves.”

Another surprise came when the researchers tested fecal samples from the animals—and found that the rats who’d learned to drive had lower levels of stress hormones than those who had not.

“It seems that driving itself is an enrichment to help with resilience,” she stated.

VMI has no laboratory animals—and isn’t likely to get any because of space limitations. Kent explained that standards of care require separate rooms for male and female animals, as well as another room for doing experiments. Caretaking, too, is an issue, as someone must come to the lab and check on the animals every day, year-round.

However, there are blood and fecal samples from the driving rats kept at the University of Richmond, and Kent said it’s very possible that those could be brought to VMI for cadets to study.

This fall, Kent is teaching a course in animal behavior. In the spring, she’ll teach an introductory course in neuroscience—and that course is already full, with a waiting list.

- By Mary Price

.svg)

.png)