Bushong Farm

“Though I am not of wealth, I have a treasury of love for you..." These are the words Jacob Bushong wrote to his sweetheart, Sarah Strickler, in 1814. Four years later on March 5, 1818, they married. Jacob built a small log cabin for his bride, which is the 1818 House today.

Of their six children, only four lived to adulthood: Harrison, a master mechanic and builder who died before he was forty; Elizabeth, a talented quilter with a keen mind for business; Anderson, a farmer like his father and the first to marry and bring the joy of grandchildren to the farm; and Franklin, an adventurous fellow who settled in the West before Civil War gripped the nation.

On May 15, 1864 the Bushong’s fertile wheat fields became a battleground. Three generations of the family took shelter in the basement of their home. After the battle, they continued to occupy the basement as their home was pressed into service as a hospital. Determined and strong, they rebuilt in the aftermath of war. The family grew as they continued to till the land.

Due to an unfortunate crop yield, the Bushong property was sold in 1942. By 1944, it was owned by George Randall Collins, VMI Class of 1911, and was on its way to becoming a permanent memorial to the VMI Cadets in the Battle of New Market. In 1964, the Bushong Farm and surrounding property was deeded to VMI, creating the first act of Civil War battlefield preservation in the Shenandoah Valley.

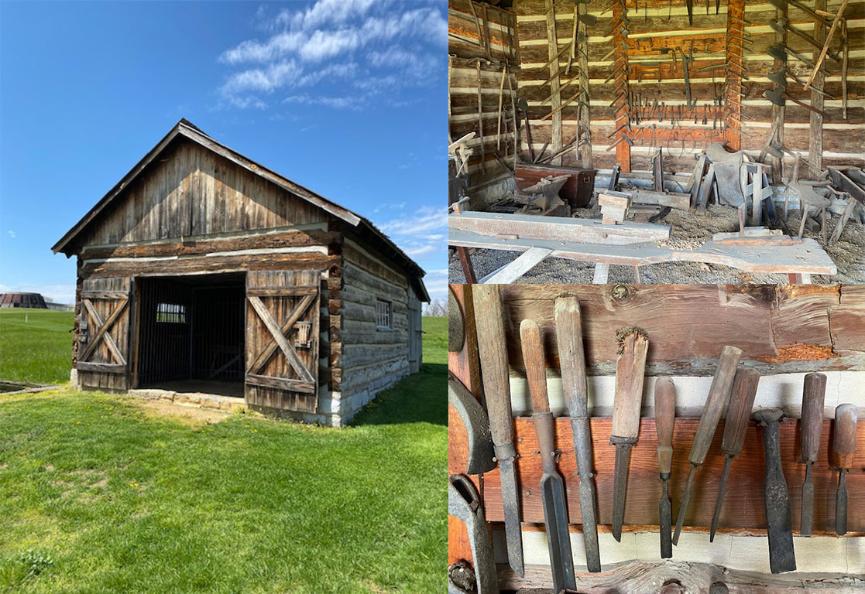

To donate to the Bushong Barn Restoration, contact the museum at 866-515-1864 Toll Free.

Reflecting their growing prosperity, Jacob and Sarah built a larger home in 1825. Their new home would face south toward the town of New Market, one mile away. As their family continued to grow, the Bushong family added to this structure, and in 1852 it appeared as it does today. By 1864, this house was the home to three generations of the family.

The house reflects the Federal architectural style (1810-1830) with a symmetrical three-bay front, pediment portico and vertical lines. Wooden clapboard construction with limestone foundation and a wooden shingle roof are common elements of homes in the Shenandoah Valley.

During the battle seven members of the family took refuge in the cellar. Jacob, Sarah, Anderson, his wife Elizabeth, Willie, Carrie and Elizabeth. Throughout the long Sunday they could hear cannon, musketry and shouts of the soldiers fighting around their home. Miraculously the house received little damage.

In 2018, VMI completed a comprehensive historical rehabilitation of the farmhouse done in large part by extensive research from original photographs. The images were scanned high resolution to reveal interesting architectural details like the type of shutter, fence construction, gutters and gates. This information was used to create historically accurate shutters, fencing and gates around the building.

Close up image of the Bushong family. L-R Jacob, Elizabeth, Sarah, William and Delilah

After the battle, the barn became a field hospital for both Union and Confederate soldiers. Remarkably Jacob Bushong’s barn was not “Sheridanized” or burned during the Shenandoah Campaign of 1864.

In a family letter written 4-23-1865 the fate of the barn is described “…Providence will still provide for us, we have never suffered for anything in the eating line notwithstanding all the barns were burned last fall and nearly everything else in the eating line destroyed[.] Your father’s barn was not burned…”

The original structure, shown in the 1899 black and white image, was struck by lightning and burned about 1:00 P.M. on Wednesday, July 6, 1939. It was rebuilt on the original foundation in 1942. It was fairly common for a farmer to have to replace a barn once or twice during his life because of fire.

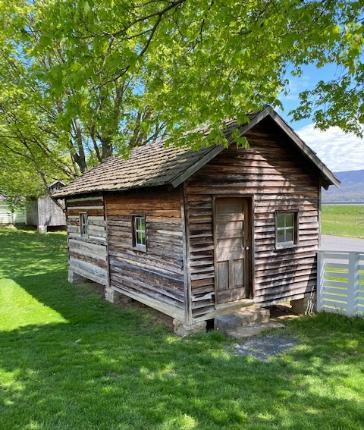

When Jacob Bushong and Sarah Strickler were married on March 5, 1818, they first built a two story log cabin facing east along the Valley Pike. For the first 7 years the young family would live here. The house was soon refined by the addition of clapboard siding.

The needs of a growing family required more space and a new, larger home was completed in 1825. When their son Anderson married, he and his new bride Elizabeth Swartz moved into the 1818 house.

-East-Elevation-300x353.jpg)

Impacted Ordnance Found - News Article from Sept. 2019

Photos of Union artillery damage found in structure in April 2019:

-400x530.png)

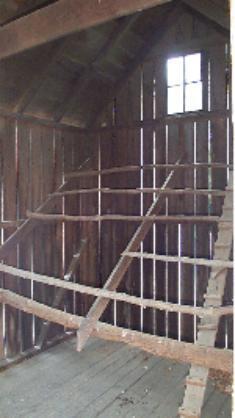

The Bushongs operated complete blacksmith and wheelwright shops which provided supplemental income for the family. Jacob’s son Harrison was known for his skill with tools and would have been called a mechanic. Farmers from the neighborhood such as Mr. Strayer or Mr. Hupp could bring their tools in for repair. The 1850 Census listed Harrison as a “machine maker” but his brother Anderson only as a “farmer” like their father.

In the 1840’s Harrison designed and built an early wheat threshing machine in these shops. He subsequently submitted a model to the US Patent Office but never received a patent for his invention.

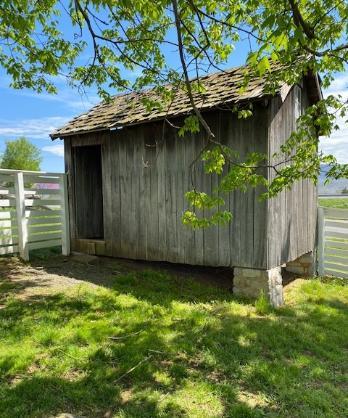

Chickens and eggs were important elements of the Bushong family meals. The daily chore of gathering eggs was shared by the youngest Bushong children. William, age four and Sarah, age six could be counted on to help with this chore. Roosters and chickens openly roamed the door yard during the day, but later moved to the perches inside of the building.

Note: The historically accurate fencing around the yard - The boards are very close together at the bottom to keep the birds in and predators like foxes out.

By the 1840’s Mrs. Sarah Bushong was buying inexpensive cloth from local dry goods merchants like J.R. Strayer & Co and making clothing for the family. During the Civil War, commercially made cloth became very expensive and scarce. Many southern families were forced to pullout ancient looms to make homespun cloth. For many women in the South homespun cloth became a symbol of both patriotism and perseverance. Mrs. Bushong originally set up their loom in the front room (frame section) and stored their meat in the back room for protection (log section).

In a letter written 4-23-1865 to son Frank Bushong, the state of the family’s clothing is clearly stated “…they still have enough to eat and to wear. Tho as to the wearing we have to make out with things we would scarcely thought fit to be seen in, now we patch and fix up the old clothes until we make ourselves believe we look right.”

Many families constructed free-standing bake ovens to avoid the heat and smell associated with the daily chore of baking. The fire was built in the oven itself. Once the brick was thoroughly heated, the ashes were removed and the items to be baked were placed in tin pans.

Many families constructed free-standing bake ovens to avoid the heat and smell associated with the daily chore of baking. The fire was built in the oven itself. Once the brick was thoroughly heated, the ashes were removed and the items to be baked were placed in tin pans.

Tools such as paddle-like peel for moving the pans, the swab for cooling the baking surface and the hoe for ash removal were vital to the operation.

During the battle, this field, just north of the Bushong House, was planted in spring wheat. It would become the site of the fiercest fighting. Five days of rain had made the field a quagmire.

During the battle, this field, just north of the Bushong House, was planted in spring wheat. It would become the site of the fiercest fighting. Five days of rain had made the field a quagmire.

As the Federal and Confederate infantry pushed back and forth through the foot tall wheat, shoes and socks were sucked from their feet by the clinging mud leaving one soldier to name this place “The Field of Lost Shoes”.

Like many families, Mr. Bushong harvested blocks of ice from small ponds during the winter. The ice was packed in sawdust and straw and stored in the back of this limestone structure. Run off from the melting ice came through a pipe and filled a stone trough in the front part of the building called the dairy. The ice house and dairy was constructed in the fall of 1871.

A family letter from Anderson to his brother Frank written January 28, 1872, tells how it was built. “…Frank we had some very cold weather and very dry (.) It pleased me very well I filled my ice house that I built last fall. I built it out of rock 12 feet in the clear dairy for milk 12 feet by 7. I set it between the pump and hen house.”

In a letter written on December 18, 1873, Anderson told his brother Frank “…I had my ice house full, and plenty of ice left for other people. I would not do without my ice house for one thousand dollars. You don’t believe how I enjoy the good cold ice water on a hot summer’s day and the best of all is the good cold milk and hard butter at mele. We made 200 l/bs butter last summer and 200 l/bs this summer, that makes 400 l/bs.”

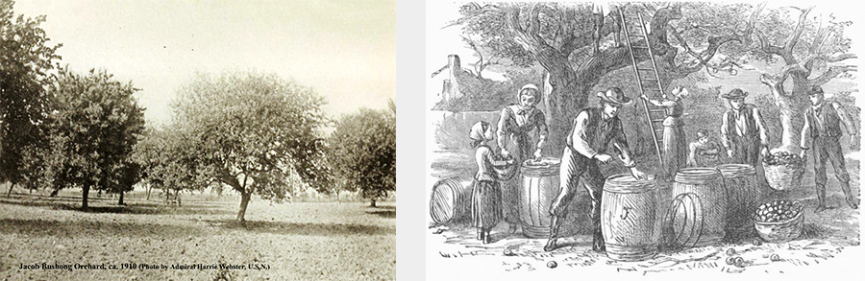

The family maintained a mixed-fruit orchard planted with several varieties of apples, peaches, pears and quince. Jacob took great pride in his yearly fruit harvest and the lucrative products such as cider and apple butter. The orchard was delineated by a rail fence described by VMI Cadet John Howard as “ordinary” and “about four feet high”.

The blossoms had just fallen from the trees on May 15, 1864 when the Confederate infantry stalled along the rail fence separating the orchard from Mr. Bushong’s northern wheat field. Around 2:00 P.M. Federal artillery and musketry fire punched a hole in the Confederate line here. It was at this moment that the VMI Cadets moved into the breech and the entire Confederate line charged across the “Field of Lost Shoes”.

The present day orchard was replanted with heirloom variety fruit trees as part of the Bushong Farm restoration in the 1960’s.

For most of the year food preparation was done here to keep food smells and dangerous heat away from the main house. The arduous process of keeping the family fed was one of the main duties for Mrs. Bushong, her daughter Elizabeth, also called Betsy and daughter-in-law Elizabeth. The family did own slaves which helped to offset the division of labor on the farm.

The earliest documentation for slaves is in the 1820 Census showing one female slave under fourteen years of age. The 1857 Birth Record for Shenandoah County showed that Jacob Bushong had one female slave named Mary who gave birth to a son named Israel. The 1860 Census showed three slaves working on the property, a 27 year old male, a 24 year old female (Mary) and a 3 year old boy (Israel). This family most likely lived in the loft above the kitchen.

Transportation was very important to the farmer. The wheelwright shop was the place to make and repair wheels for wagons and buggies. It also served as a general carpentry shop for the farm. To be a mechanic in this trade required a high degree of math and geometry. The hub had to be bored just right and the spokes mounted with just the right angle or the wheel collapses. Not every farm could boast of a blacksmith and a wheelwright shop. Farmers in the neighborhood could bring their broken wheels to Harrison Bushong to repair. This building houses a collection of woodworking tools and period farm implements.

Harrison received a letter from a friend February 24, 1851 regarding his love of the shops “…I hope this reaches you, you may again be restored to your usual health again and find you engaged in the shop the place where you so much delight to occupy.”

.svg)

.png)